Trump's new rules could swamp already backlogged immigration courts

In San Antonio, an immigration judge breezes through more than 20 juvenile cases a day, warning those in the packed courtroom to show up at their next hearing — or risk deportation.

A Miami immigration lawyer wrestles with new federal rules that could wind up deporting clients who, just a few weeks ago, appeared eligible to stay.

Judges and attorneys in Los Angeles struggle with Mandarin translators and an ever-growing caseload.

Coast to coast, immigration judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys are straining to decipher how the federal immigration rules released in February by the Trump administration will impact the system — amid an already burgeoning backlog of existing cases.

READ MORE:

These undocumented immigrants thought they could stay. Trump says deport them.

Homeland Security unveils sweeping plan to deport undocumented immigrants

5 ways Trump will increase deportations

In a border town, locals 'very fond' of their federal Border Patrol officers

Step by step: how the U.S. deports undocumented immigrants

The new guidelines, part of President Trump's campaign promise to crack down on illegal immigration, give enforcement agents greater rein to deport immigrants without hearings and detain those who entered the country without permission.

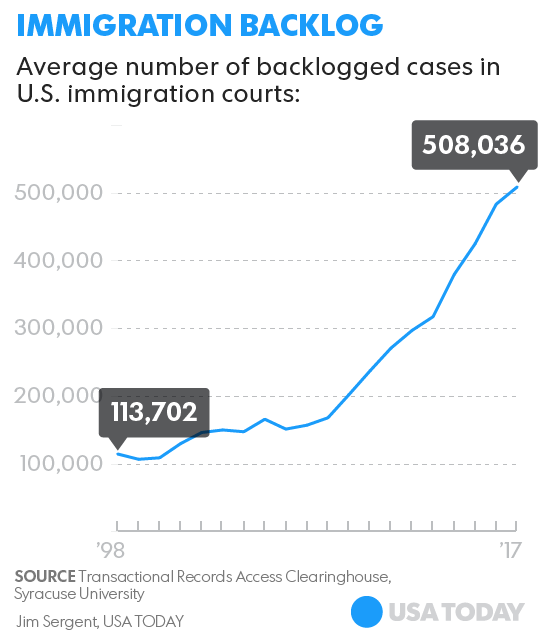

But that ambitious policy shift faces a tough hurdle: an immigration court system already juggling more than a half-million cases and ill-equipped to take on thousands more.

“We're at critical mass,” said Linda Brandmiller, a San Antonio immigration attorney who works with juveniles. “There isn’t an empty courtroom. We don’t have enough judges. You can say you’re going to prosecute more people, but from a practical perspective, how do you make that happen?”

Today, 301 judges hear immigration cases in 58 courts across the United States. The backlogged cases have soared in recent years, from 236,415 in 2010 to 508,036 this year — or nearly 1,700 outstanding cases per judge, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a data research group at Syracuse University.

Some judges and attorneys say it’s too early to see any effects from the new guidelines. Others say they noticed a difference and fear that people with legitimate claims for asylum or visas may be deported along with those who are criminals.

USA TODAY Network sent reporters to several immigration courts across the country to witness how the system is adjusting to the new rules.

MIAMI. BACKLOG: 23,045 CASES.

Cynthia Adriana Gonzalez stood before Immigration Judge G.W. Riggs and awaited instructions. She’s an undocumented immigrant from Mexico with no criminal record and three children born in the U.S.

Gonzalez’s attorney asked for “prosecutorial discretion,” a common practice under the Obama administration in which the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) didn’t push to deport undocumented immigrants with no criminal record.

The new directives vastly broaden the pool of undocumented immigrants considered for deportation. The result has been a jarring shift in which the government seeks deportation in nearly every immigration case, said Clarel Cyriaque, a defense attorney who represents Haitians in South Florida. Dozens of his clients were under consideration for prosecutorial discretion based on their years in the U.S., steady employment and clean records.

"That’s off the table now,” he said. “As soon as Trump took office, everything stopped. They got new marching orders. Their prime directive now is enforcement, as opposed to exercising discretion that would help good people.”

Homeland Security says its attorneys can still practice discretion on a case-by-case basis. But a statement released after Trump signed his executive order on immigration in January states, “With extremely limited exceptions, DHS will not exempt classes or categories of removal aliens from potential enforcement.”

In another courtroom, Judge Rico Sogocio rescheduled until September the hearing of a young Haitian man to give him time to find an attorney. Through a Creole translator, the man asked the judge what would happen if he gets picked up by enforcement agents before then.

Sogocio pointed to a sheet in the man’s stack of documents that proves he has been attending his court hearings. “I suggest, sir, if you want to be as safe as possible, you carry that with you,” the judge said.

The man clutched the document, whispered “Thank you” and walked out.

LOS ANGELES. BACKLOG: 44,596.

On the eighth floor of a skyscraper in downtown Los Angeles, Judge Lorraine Muñoz hears cases with such efficiency that immigration lawyers nicknamed her list of cases the "rocket docket."

Immigrants, clad in the orange jumpsuits of federal custody, answer questions about how and why they entered the country. Lawyers for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) aggressively examine their explanations.

One case involved a Chinese man who allegedly flew to Tijuana, Mexico, on a tourist visa, climbed over the border fence and turned himself in to U.S. Border Patrol agents. He was seeking asylum in the U.S., claiming he was persecuted for being a Christian in his rural farming village.

At his hearing, the ICE lawyer asked him to repeat his story multiple times, pointing out changes in the narrative. At one point, the man said, police officers hit him in the head after arresting him.

“Last time you told us you were only hit in the stomach and chest,” the lawyer said. “So at the last hearing you forgot where you were struck?”

His lawyer, who was filling in for another attorney and had not met this client before, did not object to the questioning.

Ultimately, the judge denied the man’s asylum request, but he had a chance to file an appeal.

Muñoz heard more cases. One detainee didn’t have a lawyer and was given time to find one. One woman didn’t have a lawyer and started to cry. Another had a sponsor but was declared a flight risk.

Translators were a problem. In one case, confusion erupted over whether people had changed their stories or misheard the translation.

Yanci Montes, a lawyer with El Rescate, a non-profit that offers free legal services, said that since the new rules were announced, prosecutors are more likely to pursue charges and deportations, and judges set higher bonds for immigrants at detention centers.

“Before Trump became president, things were a lot smoother,” she said.

Meanwhile, the cases mount. The backlog at immigration courts has spiked over the past decade as resources poured into immigration enforcement, said Judge Dana Leigh Marks, president of the National Association of Immigration Judges.

Funding for immigration courts increased 70% from fiscal years 2002 to 2013, from $175 million to $304 million, and budgets for ICE and Customs and Border Patrol rose 300% — from $4.5 billion to $18 billion — in the same period, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

“There is concern and frustration” among the judges about the latest guidelines, Marks said. “The people in the field are feeling very disconnected from the decision-makers and are not aware of much, if any, of the specifics of how these broad, aspirational goals will be implemented.”

SAN ANTONIO. BACKLOG: 26,115.

Courtroom 7 at the San Antonio Immigration Court is a small room on the fourth floor of a nondescript building near downtown, with the few wooden benches almost always full.

On a recent afternoon, Judge Anibal Martinez heard case after case of juvenile immigrants seeking asylum. They were from Honduras, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico.

Martinez smiled at the youngsters and, through an interpreter, thanked them for their patience. Of the 25 juveniles listed on the docket, just four had legal representation. About half of the kids didn’t show up.

“You’ve been excellent in bringing your daughter to court today,” the judge told one woman. “But if she misses the next hearing, I may order her removal in absentia. Whether or not you have an attorney, you must show up.” The mom nodded in agreement.

Brandmiller, the immigration attorney, said many immigrants are too scared to appear in court. “I try to tell them it’s the opposite — if you don’t show, there’s a greater chance you’ll be deported,” she said. “But there’s such a deep fear out there right now.”

A floor below Martinez, in Courtroom 4, Judge Daniel Santander called adult cases until all 20 had been heard in the course of a morning. He spent just a few minutes on each; most were rescheduled for later dates.

Then, at 1:30 p.m., he heard the case of Juliana Navarro, 51, of Chimbote, Peru, his only hearing of the day involving an immigrant in custody. Navarro said she had escaped from an abusive husband last year with her two grown children and crossed the Mexican border into the United States.

Speaking by video conference from the T. Don Hutto Residential Center in Taylor, Texas, where she was being held, Navarro detailed how her ex-husband would beat her with an extension cord and sexually assault her during their 25 years of marriage. Through sobs, she said she was afraid that if she stayed in Peru he would find her, and he frequently threatened to kill her and himself if she ever left him.

She explained how it took six attempts to cross the Rio Grande into the U.S. and how she initially gave border agents a fake name and said she was from Mexico so they wouldn’t return her to Peru. She described being held in a federal detention facility nicknamed el hielero — “the cooler” — for the frigid temperatures of the holding cells before she was transferred to Hutto.

Santander listened intently through her testimony, pausing several times to allow Navarro to sip water and regain her composure. “Take a deep breath,” he said through an interpreter. “It is not my intention to embarrass you. It is my intention to find the truth.”

After 1½ hours of testimony, Santander asked a few questions, followed by questions from the prosecutor representing ICE who wanted to know why Navarro didn’t move into one of her siblings’ homes in Peru or Chile and what role, if any, the Peruvian government played in her ordeal.

Santander thanked Navarro for her testimony and said he would write his decision and have it delivered to her. The process could take 30 to 60 days.

“What do I do now?” Navarro asked.

“You can hang up the phone, drink some water and let the officers take you back to your room,” Santander said. “Just relax. It’s in my hands now.”

Jervis reported from San Antonio and Gomez from Miami. Solis, who writes for The (Palm Springs, Calif.) Desert Sun, reported from Los Angeles.