Charter schools’ ‘thorny’ problem: Few students go on to earn college degrees

Like many charter school networks, the Los Angeles-based Alliance College-Ready Public Schools boast eye-popping statistics: 95% of their low-income students graduate from high school and go on to college. Virtually all qualify to attend California state universities.

Its name notwithstanding, the network’s own statistics suggest that few Alliance alumni are actually ready for the realities — academic, social and financial — of college. The vast majority drop out. In all, more than three-fourths of Alliance alumni don’t earn a four-year college degree in the six years after they finish high school.

Publicly funded, but in most cases privately operated, charter schools like Alliance are poised to become a much bigger part of the USA’s K-12 public education system. Yet even as their popularity rises, charters face a harsh reality: Most of the schools boast promising, often jaw-dropping high school graduation rates, but much like Alliance, their college success rates, on average, leave three of four students without a degree.

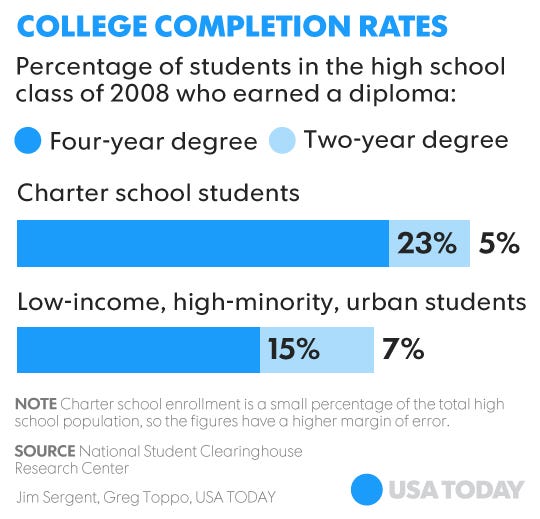

Statistics for charter schools as a whole are hard to come by, but the best estimate puts charters’ college persistence rates at around 23%. To be fair, the rate overall for low-income students – the kind of students typically served by charters – is even worse: just 9%. For low-income, high-minority urban public schools, most comparable to charters, the rate is 15%.

Charter schools must 'pivot' from original mission

So while many charter schools offer students a more viable path to high school graduation, the low college success rate in many cases is forcing the schools themselves to rethink their offerings.

“It’s time for us to pivot,” admitted Dan Katzir, Alliance’s CEO. Asked to rate the importance of raising the network’s college graduation rate, he said: “This is our work for the next 10 years.”

In many ways, charter schools were designed a quarter-century ago to help close the rich/poor college gap, though it has taken nearly that long, charter officials say, to do so for more than just a few students.

The first charter school opened in St. Paul, Minn., in 1992, and since then the sector has grown steadily. Total enrollment topped 3 million students for the first time last fall, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. More than 6,900 schools now enroll an estimated 3.1 million students, about three times as many as a decade earlier. Last fall alone, the alliance notes, more than 300 charter schools opened.

The Trump administration has floated an offer to allow even more families access to charter schools, among other choices such as private-school vouchers and tax credits. In an editorial this month in USA TODAY, U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos wrote of students stuck in “failing” neighborhood schools: “If they don’t have the means to move to a better school district, then they’re trapped,” she wrote.

'It's a big, hard thorny problem.'

Yet even educators in the charter world say that simply handing families more choices is unlikely to improve outcomes.

“It’s a big, hard, thorny problem,” said Seth Andrew, founder of Democracy Prep Public Schools, a network of 20 charter schools in New York, Washington, D.C., Camden, N.J., and Baton Rouge, La. Although its first alumni are not slated to finish college until this spring, the network has pushed hard to make college completion a priority. He estimates that nearly nine in 10 Democracy Prep alumni are on track to earn a four-year degree.

Kevin Carey, director of the Education Policy program at New America, a left-leaning Washington, D.C., think tank, said many low-income students drop out of college because they’re overwhelmed by high-level academics. Others end up at colleges that are a lousy match. Even students at colleges that suit them may suffer from a lack of guidance or difficulties integrating into social and academic life. In some cases, he said, even successful students’ families simply can't afford tuition, fees, room and board.

“Whatever happens in college that tends to prevent students from graduating, those factors seem to overwhelm whatever preparatory virtues even the best charter schools are able to impart in their students,” Carey said.

Founded in 2004, Alliance operates 28 middle and high schools throughout L.A., serving about 12,500 low-income students. It’s got even bigger ambitions: The network was part of a proposed $490 million plan in 2015 to move half of the city's students into charters. Proposed by the L.A.-based Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, the plan has been opposed by teachers’ unions and members of the city school board.

In its recruitment materials, Alliance says 100% of students fulfill all requirements for admission to a University of California or California State University college. But what the materials don’t mention is that since graduating its first class in 2008, just 22% of eligible students have actually completed college in the six years since high school graduation. Only 6% who start at two-year colleges eventually earn a four-year degree.

Katzir, Alliance’s CEO and a former Broad Foundation managing director, said the poor results should be taken in context, since Alliance’s first job, more than a decade ago, was to raise high school graduation rates.

In 2004, he said, there were 49 high schools in the L.A. school system “The reason why I remember there were 49 high schools is that the district’s average high school graduation rate at the time was 49%,” Katzir recalled.

At the time, he said, charter schools set out to prove “that you could overcome the high school ‘dropout factory’ and you could take these exact same students, provide them with opportunities and access to academic programming that enabled them to complete high school and get into college.” That first decade or so, he said, “we were built to solve a problem in urban communities that no one else had done before, which is actually get poor black and brown scholars through high school. Once we were able to do that, then the question becomes: ‘O.K., well what’s next?’”

He noted that for Alliance alumni who attend a group of 150 universities focused on aiding minority students, the graduation rate is 69%. Alliance came up with the list by ranking 4,200 U.S. schools based on their graduation rates for "underrepresented minorities," and found that just 150 had a six-year graduation rate of 75% or higher.

Many low income students less likely to earn degrees

In many ways, the college-persistence problem is not just a charter school problem, but one that afflicts low-income students more generally. In 2013, the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, a Washington, D.C.-based research group, found that students from the USA’s lowest-income families were about one-eighth as likely as the wealthiest students to have a bachelor’s degree by age 24. For the wealthiest, the rate was 77%. For the poorest? Just 9%.

The 9% figure is “just epically disappointing,” said Katie Duffy, Democracy Prep’s CEO. “A high school diploma is just not going to get our kids to the point where they can have resources and live that life of civic engagement.”

Democracy Prep schools require college counselors on all campuses to match graduates to appropriate colleges, Duffy said. Once students are in college, a “really aggressive” team of 10 alumni tracks their progress, pulling transcripts and talking to both the student and college administrators about how they’re doing.

At the moment, Duffy said, 87.5% of its first graduates, from the Class of 2013, are still enrolled in college. Of the rest, roughly one in eight, who aren’t in college, the alumni team is working to get those students back on track, either by helping them get jobs to pay for classes or by easing them back into classes through nearby community colleges.

“Some of it’s financial,” she said. “Some of it is life stuff.”

For all of their focus on academic success, most charter schools have only recently begun puzzling over college persistence. As a result, good national data is hard to find — one group of researchers in 2014 quipped that, compared the “voluminous literature” on charters’ achievement gains, research on outcomes such as college graduation “is still sparse.”

Recent findings suggest that attending a charter school will likely push students toward attending a four-year college, but the most comprehensive research so far, from the high school class of 2008, put the six-year college completion rate for charter high school students at just 23% for four-year colleges. Another 5% earned degrees from two-year colleges. Researchers cautioned that the sample size was small, however, and subject to "higher variance and uncertainty" than the much larger group of district high school graduates.

In 2009, 15 years after the popular Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) opened its first middle school — and five years after its first high school — KIPP took a good look at the fate of its alumni. They found that six years after finishing high school, only about one in five students in New York City had earned a college degree.

“It was pretty sobering,” said KIPP’s Steve Mancini.

The chain began focusing less on simply getting students to college and more on skills that would help them get through college, with an eye toward turning out graduates who could be successful after they left the heavily structured KIPP environment. “We weren’t trying to produce kids who were just great eighth-grade test-takers,” Mancini said.

KIPP pushed its high school seniors to apply to more colleges — as recently as 2014, Mancini said, only 12% applied to six or more colleges.

And they trained college counselors to match students more closely with colleges that fit their abilities.

Two years later, in 2011, KIPP looked more broadly at its alumni and found their four-year college completion rate had risen to 33%. Last year, it was 45%, with another 6% holding two-year degrees. In the most recent high school class, 73% applied to six or more colleges.

“We still have room to grow but I think that is incredible,” Mancini said.

Next they plan to take a look at issues that hold students back, such as food insecurity — they’ve already found that about 60% of college-going alumni report having to forego meals to pay for books or other necessities.

Carey, of New America, said one of the biggest problems is that many charter schools are located in economically distressed neighborhoods, so they naturally guide students to nearby colleges. But many of these — often they’re two-year public community colleges — have some of the USA's lowest graduation rates. The colleges that many charter school students end up in suffer from “many of the same pathologies as public K-12 institutions,” such as a lack of resources and lousy educational models. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that they have low graduation rates. “Particularly for low-income students, it does matter where you go to college,” Carey said.

Once they arrive, he said, colleges must step up and prepare for more students whose success isn't guaranteed. "As someone who works a lot in higher education, I can tell you: a lot of colleges are bad at that.”

So the Trump administration's plan to provide families with more K-12 choices won’t necessarily solve the graduation problem, he and others said.

“We already have a lot of choice in higher education," Carey said. "We already have a ‘voucher’ system in higher education, and yet we have a dropout problem in higher education that’s substantially worse than the dropout problem we have in K-12.”

More coverage:

Hidden dropouts: How schools make low achievers disappear

Follow Greg Toppo on Twitter: @gtoppo