Teachers who sexually abuse students still find classroom jobs

Steve Reilly

Steve Reilly

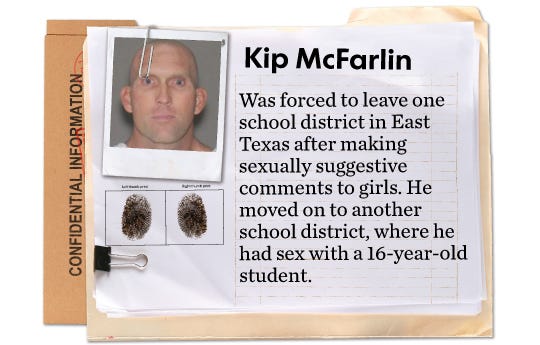

School officials in East Texas didn’t want Kip McFarlin around their students.

For years, he had crossed the line in conversations with teenage girls, using sexually suggestive language and even telling one student he’d date her if he were younger.

By 2005, administrators at Orangefield Independent School District, about a two-hour drive from Houston, had investigated complaints by six different students.

When it came time to deal with the Orangefield High School football coach, administrators didn’t fire McFarlin or report him to police. They didn’t even notify Texas education officials who had the power to take away his teaching license.

Instead, they let him become someone else’s problem.

They hid his behavior from state regulators, parents and coaches.

All McFarlin had to do was go teach somewhere else.

“This incident does not have to end McFarlan’s (sic) career,” school district attorney Karen Johnson wrote in a letter in 2005 to then-superintendent Mike Gentry. In the letter, Johnson recommended the district negotiate “a graceful exit” for the teacher.

Less than two years later, McFarlin, then 38, landed a job at a nearby school district, where no one had any idea about his past problems.

In 2011, he had sex with one of his students, a 16-year-old girl.

Despite decades of repeated sex abuse scandals — from the Roman Catholic Church to the Boy Scouts to scores of news media reports identifying problem teachers — America’s public schools continue to conceal the actions of dangerous educators in ways that allow them to stay in the classroom.

A year-long USA TODAY Network investigation found that education officials put children in harm’s way by covering up evidence of abuse, keeping allegations secret and making it easy for abusive teachers to find jobs elsewhere.

As a result, schoolchildren across the nation continue to be beaten, raped and harassed by their teachers while government officials at every level stand by and do nothing. The investigation uncovered more than 100 teachers who lost their licenses but are still working with children or young adults today.

In the most comprehensive national review of teacher discipline to date, USA TODAY examined educator misconduct and licensure databases from every state, reviewed thousands of pages of court filings and employment records and surveyed state education officials to determine how teachers who engage in misconduct remain in the education system.

Among the findings:

• State education agencies across the country have ignored a federal ban on signing secrecy deals with teachers suspected of abusing minors, a practice informally known as “passing the trash." These contracts hide details of sexual behavior and sometimes pay teachers to quit their jobs quietly. The secrecy makes it easier for troubled teachers to find new jobs working with children.

• Private schools and youth organizations are especially at risk. They are left on their own to perform background checks of new hires and generally have no access to the sole tracking system of teachers who were disciplined by state authorities.

• Despite the risks, schools of all kinds regularly fail to do the most basic of background checks. A private high school in Louisiana hired a teacher who was a registered sex offender in Texas. Students using a simple Web search uncovered his past.

• School administrators are rarely penalized for failing to report resignations of problem teachers to state licensing officials. Though 41 states have laws requiring public school administrators to report the firing or resignation of a teacher to state education officials, violations of those laws rarely have consequences.

At every level, institutions and officials charged with ensuring the safety of children have failed. Lawmakers have ignored a federal mandate to add safeguards at the state level. Unions have resisted reforms. And administrators have pursued quiet settlements rather than public discipline.

This isn’t supposed to be happening.

A series of high-profile abuse cases and media investigations in the 1990s and 2000s put a spotlight on lax regulations by government officials at every level.

A few states, including Florida, Missouri and Oregon, instituted tough laws and regulations to crack down on abusive teachers and publicly report their names. Congress passed a law in December 2015 requiring states to ban school districts from secretly passing problem teachers to other jurisdictions or face losing federal funds. But 45 states have not instituted a ban.

None of those changes closed the gaping holes plaguing the nation’s teacher screening system. Inconsistencies in state background check rules and the lack of a government-run tracking system for serious teacher misconduct continue to hinder efforts to root out problem educators.

“I’m not against what’s been put into law,” said Charol Shakeshaft, a professor of educational leadership at Virginia Commonwealth University who has studied teacher misconduct. “It just isn’t much of a solution.”

The results of the unheeded calls for change have been tragic.

Although abusive teachers make up only a fraction of 1% of the nation’s teaching corps, USA TODAY found dozens of teachers who lost one job after being accused of abusive behavior and had no trouble getting hired somewhere else.

They include a New Jersey teacher who molested five elementary school students, an Oregon substitute teacher who reached under a table to touch a student’s genitals and an Illinois teacher who forced elementary students to eat food off his crotch. In each instance, the teacher had been disciplined for sexual misbehavior in a prior school district.

Those cases were among many identified as part of a two-year investigation by USA TODAY Network into flawed screening mechanisms that allow educators with troubled pasts to work with children again in public schools and private settings. A story published this year found that the only national system to track abusive teachers was riddled with problems that make it impossible to thoroughly screen teachers as they move from state to state and was missing thousands of names.

“It’s enraging when I read these cases about a teacher who has been well-known for abusing little children for over 20 years,” said Charles Hobson, a professor of business management at Indiana University Northwest who studies teacher misconduct. “And nobody — nobody — has picked the phone up and called Child Protective Services or the police. That’s crushing.”

Reforms follow USA TODAY Network teacher probe

Though passing the trash can be the most expeditious way for a school district to rid itself of a bad teacher — often helping avoid the cost of lawsuits or the burden of fighting teachers unions at termination hearings — the consequences for students can be devastating.

In an ongoing federal lawsuit, a former student testified that New Mexico elementary school teacher Gary Gregor repeatedly touched her legs in class and invited her to sleep in his bed with him. Gregor, who has denied the allegations in the civil suit, resigned from another school district where he was accused of engaging in similar behavior. He declined to comment due to the pending litigation.

“I was a little girl. I thought I could trust adults, right?” the former student said in a deposition. “I can’t trust anyone.”

When McFarlin applied for a teaching position at the Port Arthur Independent School District in 2008, having left his job in Orangefield, school officials in the town along Texas’ border with Louisiana might have counted themselves lucky.

McFarlin, a graduate of Texas Tech with a major in exercise sport science, had more than a decade of experience as an educator. There was nothing on his criminal background check. His Texas Education license record showed no disciplinary actions.

On his application, he listed the reason he left two previous teaching jobs as “job improvement.” Port Arthur’s human resource director, James Wyble, said Orangefield school officials never told him about the misconduct allegations when contacted for a reference.

“They … shared with me that the reason that Kip was leaving Orangefield was because … there was a divorce in the family and Kip felt like he needed to move on,” Wyble said in a deposition taken as part of a federal lawsuit against both districts by the victim of McFarlin’s crime. “That’s what was shared with me.”

The lack of disclosure was not an accident.

Johnson, the attorney of Orangefield schools, in her 2005 letter to the superintendent laying out the terms of McFarlin’s “graceful exit,” advised the district to “agree to a neutral recommendation or positive recommendation for his coaching duties, etc.”

Johnson was hired in 2007 by the Texas Education Agency, which oversees teacher credentialing in the state, according to state records. Neither the agency nor Johnson responded to requests for comment.

The school district was not required under state law to disclose McFarlin’s misconduct to state officials because he was not convicted of a crime — a fact Johnson stressed in her memo suggesting the district keep its findings about McFarlin’s inappropriate comments to students secret from the State Board for Educator Certification.

“I do not feel that you have to report to SBEC under §21.006 Tex Educ Code,” she advised the district. “He is not guilty of abuse or an unlawful act with a student, just inappropriate and stupid remarks for a professional to make.”

McFarlin entered the job market with a clear history and soon landed the job in Port Arthur.

Within weeks of the start of the 2011 school year, according to court records, he had sex with one of his 16-year-old students.

McFarlin was convicted of sexual assault of a child and improper relationship between an educator and a student and is serving an eight-year prison sentence. The school administrators involved in the case were not criminally charged.

Texas is one of 41 states in which there is a law requiring school districts to report the resignation of an educator who is accused or suspected of misconduct to state education officials, according to a USA TODAY survey of education officials in every state. Texas’ law was in place in 2005.

Most of those 41 state laws, including the one in Texas, lack any civil or criminal enforcement mechanism for failing to report.

The victim’s federal lawsuit against the two school districts that employed McFarlin was dismissed in 2014 after a judge ruled the victim did not state a legally valid claim against Orangefield and did not prove that Port Arthur should have known about the prior misconduct. McFarlin, serving his sentence at a state prison outside Houston, could not be reached for comment.

USA TODAY Network found similar examples in nearly every state, and the secrecy is often cemented in legally binding contracts.

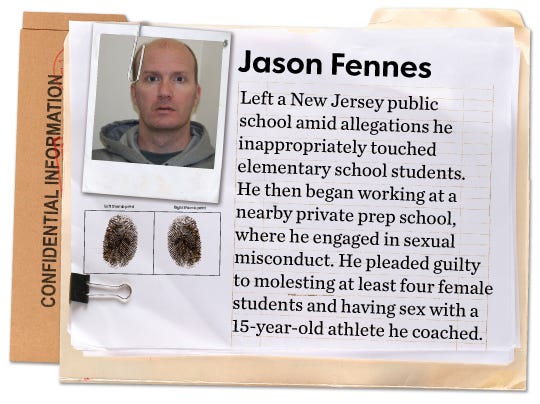

In New Jersey, Montville Township Public Schools wanted to get rid of first-grade teacher Jason Fennes in 2010 after complaints he had engaged in misconduct with his female elementary school pupils, including allegations that he inappropriately touched them and allowed them to sit on his lap.

The district did not report the accusations to police. It signed a contract stating that only his positions and dates of employment would be disclosed to prospective future employers and that “no further information will be provided.”

Less than two months after resigning, Fennes was hired for a teaching job at Cedar Hill Prep School, a nearby private academy.

Prosecutors in two counties brought charges against Fennes after victims from both schools came forward. He entered guilty pleas in both cases in September, admitting to molesting at least four female students and having sex with a 15-year-old athlete he coached.

In another case, Ohio elementary school teacher Timothy Dailey lost his license after he was accused of touching students in a sexually suggestive manner. District officials in Chillicothe, about one hour south of Columbus, took measures to keep the accusations secret. Dailey could not be reached for comment.

In a settlement agreement, the Union Scioto Local School Board agreed to transfer all documents about the misconduct into a file separate from Dailey’s personnel file. The district even agreed to let Dailey meet with the school board attorney to determine which items would be removed.

The district agreed to take no actions “which would jeopardize applications at future school districts” and that a school administrator would say “no comment” if asked about Dailey’s reasons for departure. The document, signed by then-school board president Sarah Cochenour, paid Dailey $82,929, records show. Cochenour could not be reached for comment.

In some cases, school districts agree to eliminate personnel records, making it all but impossible to tell what the teacher was accused of doing.

“These separation agreements and confidentiality agreements that allow these alleged predators to obfuscate the law and not be reported to police as they should be and stopped have created a pool of mobile molesters in our schools,” said Terri Miller, president of the Nevada-based advocacy group Stop Educator Sexual Abuse Misconduct & Exploitation.

Using disciplinary records from every state, USA TODAY identified more than 100 educators whose public-school teaching credentials were revoked or surrendered for serious misconduct yet continued to work with youth in different environments.

When reporters set out to track down the educators and the administrators who gave them their new jobs, the result was a blitz of excuses and obfuscation.

A Missouri sex offender told a reporter he was not working with teens on a youth basketball team before deleting evidence from his Facebook page.

A senior pastor at a Georgia church said the children’s pastor failed to disclose during the application process that he lost his state teaching license for misconduct with students.

An official at an Oregon community college said it did not check the state license history of an instructor whose K-12 teaching privileges were revoked for exchanging sexually graphic messages with an underage girl.

From youth sports leagues to church groups to tutoring groups, employees or volunteers are often hired with no background checks. The analysis shows how easily those accused of misconduct can dodge oversight — especially if they move into private schools or private coaching jobs.

Only nine states require background checks for volunteers in the sports activities.

In Florida, Charles Moehle lost his teaching license because he continuously texted a student, showed up at her house unannounced and gave her flowers, according to state records.

Moehle resigned his position as football coach at Pasco County Schools but remained in the classroom until he was caught months later with “multiple erotic and pornographic images” on his school computer in 2015, according to state records. He could not be reached for comment.

Eric Romig, a part-time softball coach in the Philadelphia suburbs, is accused in a federal lawsuit of a pattern of misbehavior that began with sending a student athlete at a private school thousands of text messages. The messages, many of them romantic in nature, according to the suit, led to Romig losing his position, then engaging in the same misconduct at a nearby public school in 2013, when he had a sexual relationship with a student.

David Babb, the athletics director for Pennridge School District, where Romig coached, said during a recent deposition that he hired Romig despite concerns that came to his attention during a conversation with the athletic director at the private school about Romig’s texting.

“He said, you know, ‘He's coached softball for me. He's doing a great job now.’ He said he had an issue with him texting,” Babb recalled in the deposition.

“What did he say the issue was?” the attorney pressed Babb.

“He did not say,” Babb replied.

“Did you ask him?”

“No,” Babb said.

In an ongoing lawsuit, the student testified that Romig gradually gained her trust by telling her details about his personal life and encouraging her to do the same — a process known as “grooming.” Eventually, she said, Romig convinced her they were a couple and said he wanted her to marry him and stay at home instead of going to college. The lawsuit’s allegations against the two schools were dismissed by a judge because the plaintiff was not able to establish their negligence, while the civil case against Romig remains active.

“He manipulated me, and he earned my trust,” the victim said in a deposition. “He kept, like, saying that he could be there, and he just earned my trust and kept trying to build up the relationship.”

The federal government does not maintain a database of teachers who have sexually abused children, and most states store data on predatory teachers within broader databases that include professional discipline imposed for paperwork deficiencies or other lesser offenses.

In the absence of a national, government-run data-sharing system to track problem teachers, state education agencies in all 50 states share information through a database maintained by the non-profit National Association of State Directors of Teacher Education and Certification, known as the NASDTEC Clearinghouse.

Private schools cannot submit information to the NASDTEC Clearinghouse. Even when misconduct is properly reported to the database by public schools, new employers don’t always check it.

In one such case, George Offenhauser Jr. was stripped of his license to teach in Texas public schools in 2001 after his second conviction on an indecent exposure charge, records show.

Offenhauser was required to register on Texas’ sex offender registry, and his name was entered by Texas education officials into the NASDTEC Clearinghouse.

None of that prevented Offenhauser from getting work when he found his way to Louisiana in 2006 and got hired to teach at a private school in New Orleans.

Broken discipline tracking systems let teachers flee troubled pasts

About 10% of the nation’s K-12 students attend a private school.

Officials at the private school were not aware of Offenhauser’s past, records show, until students searched the Internet while trying to find a picture of him for a school event and stumbled upon his entry in the Texas sex offender registry.

Despite learning of his sex offender status, school officials did not contact law enforcement, allowed Offenhauser to continue teaching and gave him a positive letter of recommendation at the end of the year, according to a report in 2010 on teacher misconduct by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, Congress’ watchdog agency.

Though most states have laws in place requiring licensed public-school teachers to undergo background checks, private schools typically aren’t required to conduct background checks under any state or federal law.

Offenhauser used this loophole to flee his past twice. After his history was discovered at the Louisiana private school, he taught for several months at a public high school outside New Orleans in 2007 before a parent accused him of sending sexually inappropriate messages to a student, according to a report by federal investigators. Offenhauser could not be reached for comment.

The problem is not new.

Going back to the 1960s, officials in the Philadelphia Archdiocese knew Raymond Leneweaver had a documented history of molesting young boys, according to a Philadelphia grand jury report citing an internal archdiocese memo. Administrators allowed the pattern of abuse by shuffling Leneweaver from parish to parish.

The archdiocese knew Leneweaver started to teach in Philadelphia-area public schools in 2003. Church officials did not prevent Leneweaver from working in four separate public school systems. Leneweaver died in 2015.

In the 1990s, Gregor — the New Mexico teacher whose victim testified he damaged her ability to trust others — was accused of sexually abusing three of his female elementary school students while teaching in Utah. One student accused Gregor of rubbing her buttocks, kissing her and telling her he loved her and wanted to marry her when she turned 16; another student said Gregor rubbed and kissed her thigh. School officials sent him off with a letter of reprimand and a $10,000 severance payment.

After a stint teaching in Montana, Gregor found work in Santa Fe, where he was again accused of misconduct with students, including hugging and tickling girls and having them sit on his lap. He resigned in exchange for a promise by school administrators to give a neutral reference.

After finding work at another New Mexico school district, Gregor finally lost his teaching license when parents told administrators that Gregor invited students to his house overnight, gave them gifts and engaged in physical sexual misconduct. One girl reported to administrators that Gregor regularly touched her legs and inner thigh, licked or kissed her on the ear and put his thumb inside her pants to touch her bare skin.

Gregor, who could not be reached for comment, has filed legal responses vehemently denying the accusations against him in the ongoing federal litigation.

In 2005, public school administrators in McLean County, Ill., gave Jon White a glowing letter of recommendation after he resigned following allegations of sexual misconduct, and he soon began working at a district nearby. He pleaded guilty in February 2007 to aggravated criminal sexual assault of 10 children across the two districts where he worked.

“I’m glad we took the steps we did to get him out of the district,” McLean Human Resources Superintendent John Pye wrote in an email to the head of the teachers union after White’s arrest. “I believe it was you that said he was on a path to further problems.”

The first school district’s findings of misconduct involving White were not reported to the Illinois State Board of Education, the state agency charged with disciplining teachers, or the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services.

Three school employees were sentenced to a $2,000 fine, community service and 18 months of court supervision. It was the only case identified by USA TODAY’s review in which administrators faced any criminal penalties for failing to report a teacher’s misconduct to state authorities.

Student welfare advocates said they have seen some progress in ending secretive practices surrounding educator misconduct, but it is not enough to eradicate the problem.

In late 2015, Congress enacted a federal law that requires each state to pass a law or regulation banning the practice of passing the trash.

The new prohibition applies to cases in which a teacher engaged in “sexual misconduct regarding a minor or student in violation of the law.”

Only Connecticut and Texas have taken action to comply with the requirement in the year since it has been in effect. Three states — Missouri, Oregon and Pennsylvania — had laws in place prohibiting confidentiality agreements before the federal requirement. In the other 45 states, movement to comply has been slow.

Some teachers organizations have consistently fought against such state legislation.

“This will limit the ability of employees and employers from negotiating separation agreements and could potentially result in a flood of teacher termination hearings,” Jan Hochadel, president of the union representing about 15,000 Connecticut educators, testified at a hearing on a new state law eradicating secret settlement agreements for teachers.

The measure passed in March with only one dissenting vote.

Efforts to maintain better national data on teacher misconduct and keep track of the worst sexual-misconduct offenders have been hamstrung by opposition from a host of state and national education groups.

One such measure, the Student Protection Act introduced most recently in 2009, would have required the U.S. Department of Education to maintain a national database of educators who are terminated from a public or private school, or sanctioned by a state government, on the basis of an act of sexual misconduct against a student. The bill died amid fierce opposition from national teachers organizations, which had concerns about due process for teachers accused of misconduct.

Shakeshaft of Virginia Commonwealth University said passing the trash is not just a product of the flawed regulations that allow it to happen but of poor judgment.

School administrators are often slow to believe a teacher’s transgressions may be a sign of a more serious pattern of abuse, allowing them to rationalize decisions to quietly shift the danger to another community.

“It’s not that they don’t believe it would happen,” she said. “It’s just that they don’t believe it would happen in their district."

Contributing: Paul Berger, Jessica Campisi, Jacob Carpenter, Mark Nichols, Nick Penzenstadler, Christopher Schnaars, Laura Ungar and Alison Young.

About this story

Through requests filed under the open records laws of each state, the USA TODAY NETWORK obtained databases identifying tens of thousands of teachers who have faced disciplinary actions.

Over the course of several months, reporters narrowed the data from each state to several thousand cases nationally in which the teacher lost or surrendered his or her public school teaching credentials due to inappropriate behavior with children or teenagers, including sexual misconduct or harassment.

The names and other identifying information for those teachers were then compared to various public databases, social media networks and other sources to identify more than 100 cases in which the teacher continued to work with youth in another environment after their public school teaching credentials were revoked or surrendered. In most cases, reporters also contacted the educator and their new employer to verify a teacher’s identity.

Read more about how we gathered and analyzed the data and how we surveyed and compared states' policies for tracking teacher discipline.