Move over, 4K – HDR TV is here, and it’s gorgeous

If you love TV technology, you probably remember the growing pains of every phase flat-panels have been through over the last decade. First was the "dieting" phase, where bezels and everything got thinner—but every gadget does that. Next, you had the awkward, fumbling first attempts at internet-connected smart TVs, and then a big industry wide push for 3D movies at home. Over the last couple years, 4K/UHD has moved from buzzword to mainstream, and has been replaced by yet another confusing acronym: HDR.

Unlike certain smart TV iterations and gimmicky 3D, nothing is going to come along and usurp 4K. It's not so much a format or feature as it is a natural extension of TV evolution. The average screen size keeps going up, but eventually you're bucking up against traditional room size. The idea to quadruple the pixel count may seem like the biggest gimmick yet, but it's not so much an end as a means.

As it turns out, 4K resolution was more of a red carpet rolled out to set the stage for something much more impressive. HDR has grabbed the spotlight as another addition to 4K.

When manufacturers and TV installers/dealers talk about HDR, there's a big desire to educate consumers. But a phrase I keep hearing is "not just more pixels, better pixels." Manufacturers and content providers keep saying, "4K was more pixels, HDR is better pixels." It totally sounds like it could be yet another hollow marketing catchphrase. This time, however, it's actually spot-on.

"Better pixels" means redder Coca-Cola.

The classic red of Planet Earth's most popular soda is one of those super-vibrant hues that traditional TVs actually can't display. This is because TVs use additive color—they add primary colors together—in this case red, green, and blue—to create other colors. Coca-Cola red calls for Red = 254, Green = 0, and Blue = 26. You can go make that color in Photoshop right now, and you can select it on any standard RGB color picker. But would you believe most entry-level, consumer-facing displays can't actually create that color?

A lot of this has to do with delivery methods. Any photographer or graphic designer knows the raw RGB format takes up a lot of information. If everything online was pure RGB, page load times would feel like dial-up. To deliver terrestrial and eventually satellite video signals to the first TVs, the information captured on camcorders and cameras had to be compressed. In pure RGB terms, standard TVs (known henceforth as "SDR" TVs) usually don't even display step 254, they are capped between step 16 and step 235, leaving so-called "headroom" and "toeroom" for video mastering and the like.

There's about 1,000 more rabbit holes we could get lost down (if you can find them in all the weeds), but the gist of it is this: HDR TVs mean you can see the classic red of Coca-Cola cans, double-decker London busses, and a lot more. This is because High Dynamic Range calls upon a wider spectrum of color saturation. While content creators eventually hope displays will be able to display a color space called "Rec.2020," today's HDR TVs are aiming for a color space called "DCI-P3." This 'digital cinema' space makes for more colorful reds, greens, and blues.

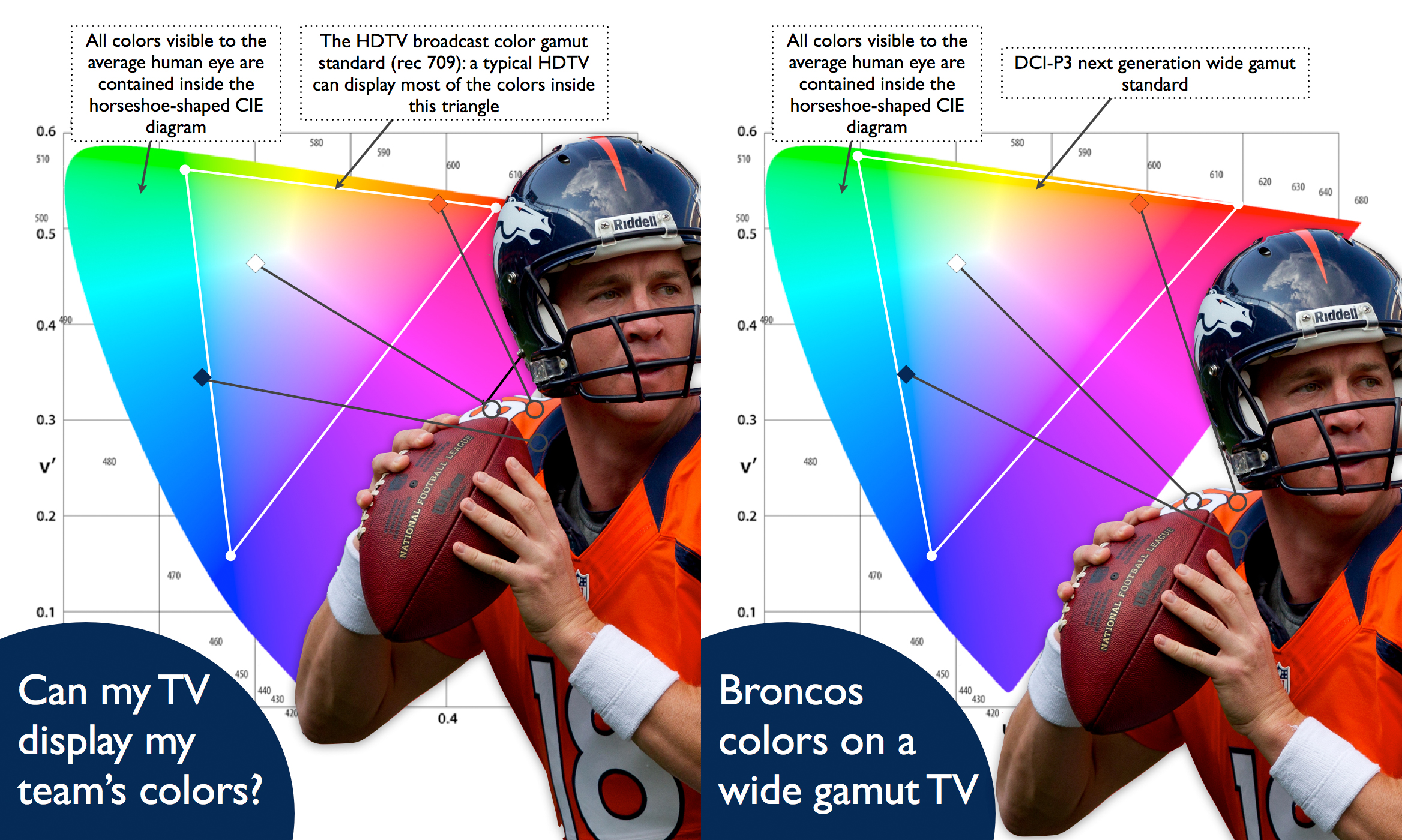

"Better pixels" means prettier Denver Broncos.

Not only do HDR TVs boast more "saturated" (read: colorful) colors, they can also produce more colors. This has to do with my favorite display/color-related concept, "chromatic resolution." While it sounds like a magical artifact from Lord of the Rings, chromatic resolution refers to the amount of color information contained in a signal. For example, SDR TVs are (typically) only capable of displaying 8-bit color. This means each of the three color channels has 8 bits of color memory, ultimately allowing for about 16 million colors.

By comparison, HDR TVs should (and will) be capable of 10-bit color depth, which allows for over 1 billion colors. It's a gigantic difference, and means content creators and mastering processes have a much, much bigger pool of potential colors to work with. It also means "enough" color for something as granular as 4K resolution. With a 4K TV, you have 8.2 million pixels, roughly half the amount of colors available in an 8-bit system. Imagine a finely gradated image—a sunset, for example—and try to imagine how real it would(n't) look if two pixels had to share the exact same color information.

The higher expression available to 10-bit displays doesn't stop at gradations, either. This expanded color granularity means subtler "steps" between colors as they travel from the dimmest to the brightest iteration. This means that even when employing much more saturated colors—like with Coca-Cola red, or say, the orange hue of the Denver Broncos' jerseys—HDR TVs are still capable of a subdued, realistic colorimetry. Basically, if you want a taller, longer staircase (more saturated colors) and you don't want to make the steps bigger, you have to add more steps.

"Better pixels" mean a doof-ier Doof Warrior.

The biggest selling point of HDR is the brightness it promises. It's hard to overstate just how striking an HDR image can be, but it's the most impressive thing about the new video format. Take a recent smash hit like Mad Max: Fury Road. There's a character in that movie called the Doof Warrior, who plays a chrome-dipped double-neck guitar that shoots jets of fire while riding atop a truck made almost entirely of guitar amplifiers. It's a ridiculous spectacle, and frankly, it's one that needs High Dynamic Range to really look its best.

Mad Max is one of the first movies to be mastered in High Dynamic Range, so it's all over the tech demos. I've watched it on VUDU in Dolby Vision (a kind of HDR), on 4K Blu-ray in the HDR10 format (again, a kind of HDR), as a regular 1080p SDR Blu-ray, and in the cinema. The difference between the HDR and non-HDR versions is night and day. This is because the Standard Dynamic Range presupposes a maximum luminance of 100 nits, based on the extremely limited capabilities of old CRT displays.

With HDR, content mastering and color grading assumes a much higher threshold for brightness. This means sun-sparkling chrome tailpipes and the rich, roaring flames of the Doof Warrior's guitar are much more striking in their brightness (relative to the rest of the image), while the dark, shadowy areas are just as dark (if not darker).

You might be thinking, "What a load of baloney. My TV is way brighter than that. It might not be as bright as HDR, but it can get a hekuvalot brighter than what you're saying." And it can! You are correct. However, it isn't meant to get that bright. It doesn't have the muscle to properly fill the volume between the bright ceiling and the shadowy floor with light and color without sacrificing somewhere.

The brighter lights of modern TVs do mean more saturated versions of recorded colors, but often at the expense of low-light color accuracy and/or saturation. This is because the content you're watching isn't graded to take advantage of such high contrast, and is going to be stretched somewhere: you can have rich low-luminance colors or flashbang high-luminance colors, but often not both.

Professional calibrators have been turning down TV backlights for years in an attempt to not "outpace" the content on display, to maintain a balanced and accurate presentation. With HDR content, we no longer need to clip wings. Instead, the target for luminance and color saturation is actually way ahead of what any display can do right now.

"Better pixels" doesn't mean worse prices.

At this point, it's pretty apparent that HDR—a healthy combination of way better contrast, color representation, and 4K resolution—is the current future of TV tech. We've been moving towards more color, higher resolution, and brighter backlights for decades. And now that Hollywood and content distributors are making content that's good enough for TVs, we no longer have to worry about driving our Ferrari-level TVs on what are essentially unpaved dirt roads. But the good news is that it looks like there's nothing but smoothly-paved highway ahead of us.

That doesn't mean you'll have to pay an arm and a leg to drive on them, though. Yes, HDR TVs are amongst the priciest right now, but it was the same way with 4K sets a few years ago; and 1080p before that; and 720p before that.

It's short-sighted to think "affordable" HDR won't be here by this time next year, in as much as a big, fancy flat-panel TV can be considered affordable. Unfortunately, some consumers are going to pay more than they probably should. That's the other thing about consumer electronics that never changes. It happened with 4K, and OLED, and everything else to hit the scene since the Sony Trinitron (RIP).

"Better pixels" doesn't mean you have to make a decision yet.

The scope of the developing HDR ecosystem (which extends from the cameras in Hollywood, to content creators and streaming partners, to your TV at home) all but ensures two facts:

- HDR is not a passing fad, it's an inevitability.

- There's never a "best" time to buy an HDR TV.

TVs are just going to keep outdoing each other. They will continue to get bigger, brighter, more colorful, with faster refresh rates, better smart features, slimmer bezels, and slicker remote controls. That's the race, and it's the reason any of this stuff is even remotely affordable, too. You can always assume you bought something too soon. If you wait too long, you might be buying too late, just before another major upgrade. There's really no perfect time for each individual person.

That said, there's really not much to watch right now. I've reviewed a couple modern HDR TVs within the last month, and I have access to TV shows and movies graded for HDR10 and Dolby Vision (the other HDR format), but with 4K HDR Blu-rays becoming more commonplace, and streaming options opening up, the content situation is improving every day.

But it's extremely, extremely unlikely that any HDR TV you buy in 2016 is going to look anything other than amazing—even in 3-5 years. It'll certainly be ready for all the content that's coming. So should you buy an HDR TV? Maybe. If a future with brighter brights, deeper shadows, and more saturated colors appeals to you, then you'll want to keep your eye on the HDR horizon.

This article originally appeared on Reviewed.com.